Magical Girl Madoka Magica is an excellent show, and you can watch it on Netflix. The following is not a review of the series so much as a tango with some of its themes. Spoilers abound.

The men in Magical Girl Madoka Magica are weak, to start off on a gendered foot. There's three of them. Madoka's brother is a helpless toddler; Madoka's father is a stay-at-home dad who needs his daughter's help with everything; Kyosuke is crippled and depressed, unable to take care of himself. At a glance, these three seem robbed of agency. Meanwhile the women make all the decisions, do all the battle.

So is Madoka a tale of the world turned upside down, a tale of warrior women saving the day?

We have to remember that the women don't actually choose these battles. They're only in this predicament because the metaphysics of the show are predicated on the essentialist (and rather suspect) claim that humans reach the peak of their emotional energy when they're thirteen years old and female. That claim is delivered to us not by a human mired in subjectivity—it's explained as a matter of fact by QB, an alien of superior intelligence who has no stake in misogyny. He's just talking about the objective conditions, so it's okay, right?

Wrong.

No matter how much I appreciate QB's anti-humanist philosophy, no matter how much I agree with the conclusions of his species if I grant them their premise, ultimately the foundations of this entire story are sexist foundations. If the story is an empowering one it is despite QB's science, not because of it, nor independent of it.

Madoka is a successful story in a lot of ways, to be sure.

It is successful fantasy.

It is successful dystopia.

It is successful noir.

It is successful romance.

But ultimately, the draw of Madoka is its indulgence in suffering.

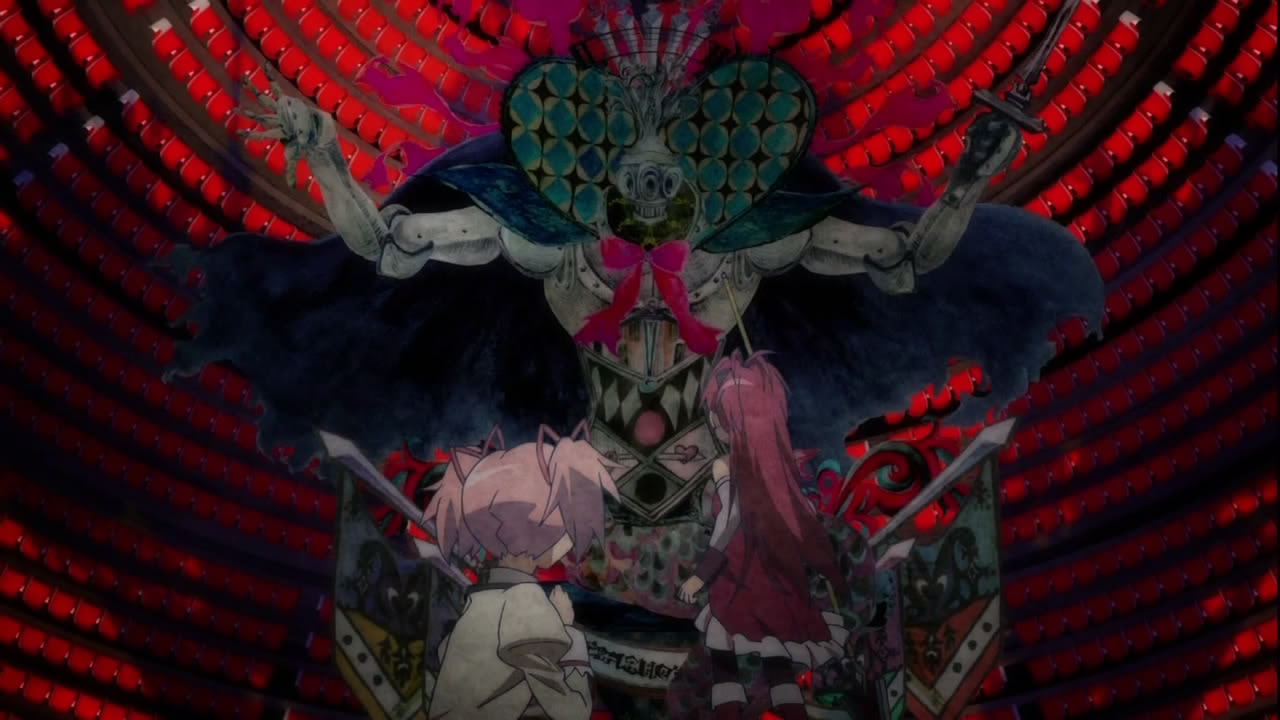

It's not unlike the Key Visual Arts/Kyoto Animation collaborations—Air, Kanon, Clannad—"emotion porn." The final film goes even further than the TV show, delivering in spades on Homura's every grimace with anime's premier twisted emo lesbian narrative. No matter how unethical the actions of, say, Hazuki in Yami to Boushi to Hon no Tabibito, no matter how melodramatic the antics of the entire cast of Maria-sama ga Miteru, none of those girls turned into Evil itself.

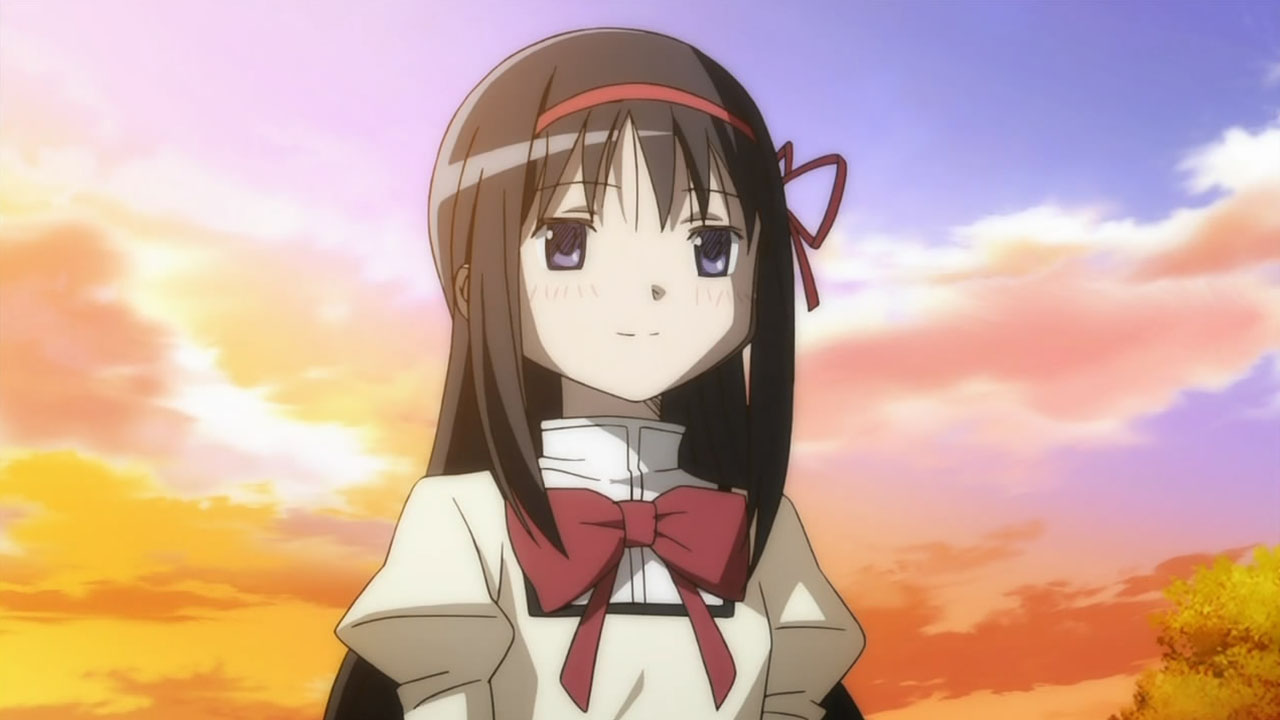

How does Homura get there? She repeats a period about a month long over and over again, endlessly throwing herself and her emotions under the bus in order to "save" Madoka. She does this, of course, because she loves Madoka.

Class S is an old Japanese fiction genre that has metamorphosed into a trope that both defines and plagues modern yuri (girls' love) works. According to it, young girls naturally form deep, nigh-romantic relationships with each other which help them socialize and learn what love is like. Eventually, they outgrow the phase (they "graduate" from it!), and this "schoolgirl lesbianism" dies sometime between the ages of seventeen and nineteen. Homosexuality within these bounds is acceptable; homosexuality beyond it is an aberration. These ideas persist today. Try naming ten unambiguously lesbian adult characters in anime who are neither villains nor comic relief.

Homura's feelings for Madoka appear to fit the mold, but Homura never grows out of this phase, despite consciously living years and years of magical girl hell. She and Madoka both still look like junior high students, but Homura is for all intents and purposes an adult. Not only have her feelings lasted longer than they should—Homura never graduates—but we actually see the natural conclusion of these feelings unchecked: insane, chaotic evil. When lesbianism is allowed to outlive youth it can only yield horror.

So is Madoka regressive?

Curiously, it actually hedges its analysis of Homura and her romance simply by being anime. Anime sells characters. It sells characters the audience loves to love; it sells characters the audience loves to hate. Most importantly it sells moe1, and Homura carries that in spades. She has gap moe2, all kinds of appearance moe3, and, most notably, she's an extreme yandere4, going so far as to shatter a benign god in order to hold the girl she loves.

Homura is an interesting character from the first time she opens her mouth ("I'm feeling nervous," she says unconvincingly, rejecting the friendly advances of her new classmates in order to go harass Madoka), and she's the kind of character whose execution can excite the audience. (If you haven't, rewatch the show, knowing her feelings. Every single facial expression takes new meaning.) She's marvelously animated, marvelously voiced. Her own transformation from helpless fangirl to determined badass is also compelling. She's just a great character, period, and she's sold well by the show. Having been sold, she in turn sells fanart, fan comics, merchandise of all varieties. It doesn't hurt that she's really tapped into writer Urobochi Gen's Equilibrium obsession, and that magical girl fans have wanted another chick with a machine gun ever since Takamachi Nanoha went all Belkan5.

Part of being sold is a commodification of every aspect of the thing being sold. Homura is anime, and anime is databasic. Every key:value pair gets commodified, to someone. And "AkuHomu," (Homura-as-Devil), is no exception. Fan works exist that make her evil aspect cute, show it frolicking with "MadoKami" ("Godoka," Madoka-as-God). AkuHomu is something customers want. AkuHomu is, in a weird way, good. And that particular good simply wouldn't exist if she weren't horribly evil.

Excessive girls' love is forgivable, it seems, if it turns a profit, even if it ends salvation.

Or: Homura is saved from judgment for her lesbianism by being a tool of profit.

Just as two wrongs rarely make right, two regressions do not progress make. Maybe in the radical landscape of left-wing fandom, AkuHomu can be read as an emblem of a societal ill. Maybe her love itself could even be celebrated, or at least criticized for the right things (her unhealthy clinginess to and assumed ownership of Madoka).

I would argue that feminism can't reach a final, perfected stage without a queer agenda. No feminism without lesbians. Girls need to be allowed to love themselves and each other before they can call themselves free. No matter the extent of gender role switching in Madoka, ultimately we see the girls falling prey to the patriarchy. Homura can never have Madoka because her love is evil. Sayaka loses everything, but especially Hiromi, her female friend, over a guy. Madoka's mom's narrative is inextricably intertwined with (unseen) male leadership. There are other examples.

Is this a normative depiction of business as usual, or is it a critique? It can be so hard to tell with anime, as it's often subtle. Equivocation abounds, even on basic plot points—what does the final scene of the Madoka film signify? Is Lelouche alive?!6

To me, Madoka feels like an attempt at critique. And not a total failure. In some ways, the entire witch system can be read as commentary on how hard life is for young women when they're defined by external forces. After all, do we not feel for Madoka when she cries about the world's injustice? And in her ultimate rebellion, does she not challenge that injustice?

Or does she merely run from reality with her wish?

She could have wished to end entropy. She had the power. QB might have considered it, but the rules prevented him from suggesting wishes. Rules are stupid. Together, QB and Madoka could have ended suffering, but they were pitted against each other by humanism and inflexibility.

One more note...

If we assume Madoka's ascension is a net positive event, then we have to thank Homura for her love. It was her special brand of timeless yandere that slowly developed Madoka into the strongest magical girl.

The problem being, of course, that Homura still loved Madoka after the ascension, and that the series writers couldn't let her move on, because Homura moving on isn't a big-budget feature film.

Amen.

While I am probably not against moe, being a fan of K-On! I’m on board with you on how regressive this franchise is. I should never bought into its progressive pretensions (I may have, all those years ago).

Whatever progressive thing it’s outwardly pushing is undermined by all the things it indulges as fetish.

Hey!

I’m a fan of K-on! as well… and I’m still a fan of Madoka. I also think it’s not on consumers to not have “bad desires.” We like what we like, and we can certainly be cognizant of any problems there. “Against Moe” won’t be a blog about how bad anime fans are, but rather a blog about how bad anime producers are 😉

(I think K-on! actually has better politics than Madoka, hilariously; maybe that’s a longer topic for another time.)

Damn right it does.

And yes. Let’s not punish ourselves lol. We like what we like.